VANISHING SANDS: MONTENEGRIN RESORT ISLAND THREATENED BY COASTAL EROSION AND GOVERNMENT'S INDOLENCE

Nature’s delicate balance disrupted by development spree, Montenegro risks losing an iconic island of 515 hectares and kilometres of sandy beaches. The shrinking of Ada Bojana threatens its unique ecosystem.

Shyqyri Kahari was once sailing the world for living – until his marriage in 1979 brought him back to his hometown of Ulcinj in Montenegro and a job on a triangular-shaped island called Ada Bojana.

Located at the border between Montenegro and Albania, Ada Bojana is flanked by the two-pronged river Bojana, while the Adriatic seafront side is blessed with a 2.9 km sandy beach. The place is popular with kite surfers, nudists, Belgrade's nouveau riche and a growing number of foreign tourists due to favourable winds and good vibes it radiates. Nonetheless the island is shrinking.

“When I started working, my little house, from which I rented out beach furniture, was 85 metres from the sea,” Kahari, a 76 year old pensioner, recalled. “But today, it’s gone. It would be under water. The beach is 85 metres shorter”. And it’s not only Kahari’s old house.

“The Ada's popular Disko Restaurant used to be about 100 metres away from the sea while today it is literally in the sea,” said veteran tourist guide and Ulcinj publicist Ismet Karamanaga. “We should be alarmed by all of this” he said. “I don’t know whether future generations will live to see the beach on Ada.”

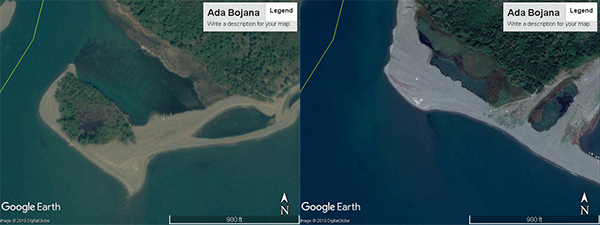

Satellite data confirmation

Schoolchildren in Montenegro are taught that their country is of 13,812 square km in size, bigger than Lebanon or Cyprus, but slightly smaller than the Bahamas. Nevertheless, this land of soaring mountains, bays and beaches is getting smaller by the day.

Some 200,000 m2 of Montenegro’s beaches have already been lost to coastal erosion. Furthermore, building of river dams and reservoirs in the hinterland and stopping and diverting of fords and rivulets that used to feed the coastline with sand and gravel has made things worse. Commercial developments have taken place of the former marshlands thus depriving the sandy shoreline of its natural buttress.

The Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) and the Centre for Investigative Reporting of Montenegro (CIN-CG) find out that the authorities’ efforts to halt the erosion have been sporadic and inadequate by far.

Ada Bojana’s retreat is visible to the naked eye.

“Satellite images confirm that Ada’s beach has significantly lost ground to the sea over the last 30 years. while the beach on the eastern part of the island is virtually gone” said Dzelal Hodzic, the executive of Green Step, an environmentalist NGO.

“The impact of strong southern waves, sea currents, reduced inflow of sediments, sand erosion and callous authorities – all these contribute to ongoing retreat of one of the most beautiful beaches on our coastline,” Hodzic told BIRN/CIN-CG.

Fatmir Gjeka, director of Ulcinj Tourism Office, said: “This should ring alarm bells both in Montenegro and in this city as our greatest resource- the sandy beaches are under imminent threat. We must focus on the causes and fight the erosion”

Unique ecosystem

Besides, a very unique ecosystem of Ada Bojana is also under threat as well as the wider area around the mouth of the Bojana River. The island and the nearby Long Beach (12 km of sandy shoreline) that stretches up to the town of Ulcinj are home to some 500 plant species, of which 23 are protected by law.

Some 250 different bird species are present in the area. Most of them are formally protected and 57 species feature in the European Union’s Birds Directive which defines standards of protection and their habitats in Europe. Over 100 different fish species populate the sea and the delta. It is one of the last Mediterranean places with psammophyte- a vegetation unique to dry, sandy habitats.

The Albanian side of the river is included in the 1971 Ramsar List, an international convention on protection of wetlands. The river itself is the third largest tributary on the European part of the Mediterranean.

The genesis of Ada Bojana goes back to mid 19th century when Merito, a Dalmatian ship under Captain Naporeli, sank between two small islands thereby blocking the river’s free flow into the sea and piling up the sediments and sand carried by the river. Around 1882 the island in progress was already visible.

However, the reversal started by construction of several dams and hydro power plants on the main tributary of the Bojana, the river Drim in Albania during the 1960s, 1970s and the early 2010s. Experts estimate that the outflow of deposits into the sea has decreased by about 30%. Moreover the commercial sand extraction had no limit. The Bojana’s flow is also disrupted by waste dumps on its edges and construction of some 600 holiday homes on the Montenegrin bank of the river.

“The dams and reservoirs have altered the Drim river course completely” said Belgrade-based professor Sava Petkovic to daily Vijesti last October. “Thus the depositing of sediments has been disrupted as well”.

Furthermore, back in 2009, the renowned German biologist Martin Schneider-Jacoby (died in 2012) told Vijesti: “It is realistic to expect that Ada will disappear in 50 to 60 years if no action is taken under current circumstances. Optimists say it may happen in 100 years. However, the end is just around the corner”.

Urge for systematic, coordinated response

Nonetheless the authorities have had no response for years except to sit and watch despite the threat to tourism industry which is pivotal to Montenegro’s economy. The government’s Coastal Zone Management Agency of Montenegro warned in July 2018 that the shrinking and vanishing of beaches may have inconceivable consequences for the country’s tourism. However the agency admitted that the efforts against the beach erosion could be labeled as “doing nothing”.

It was stated in National Strategy of Integrated Coastal Zone Management in 2015 that it was impossible to ascertain how quickly the beaches were eroding “due to lack of systematic monitoring”.

Predrag Jelusic, the director of Coastal Zone Management Agency, confirmed that in some parts of Ada Bojana the beach line had receded by 80 metres.“The beach at Ada Bojana is losing ground to the sea at considerable pace” Jelusic told the members of Parliament last December.

Environmentalist groups say that indolence amounts to grave irresponsibility.

Jelena Marojevic, a programme coordinator with Green Home- an environmentalist NGO, said the root of the problem was the water (mis)management in the Drim basin. Civil sectors in both Montenegro and Albania “tried on several occasions to alert the authorities as well as as general public and experts” Marojevic told BIRN/CIN-CG.

Petkovic, in his interview with daily Vijesti, called for a full scale cleaning of the Bojana riverbed “as only that can somewhat halt the beach erosion in Ulcinj”.

Island-turned-peninsula

Decades of neglect came to fruition in August 2017. The Bojana could no longer flow into the sea and the island temporarily became a peninsula. The government finally started dredging the riverbed and freeing the passage to the sea. About 5,000 m3 of deposits extracted from the closed river mouth was used to “nourish beaches” in Ada and the Long Beach.

Milutin Simovic, Montenegro’s Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, said that both Montenegro and Albania would conduct proper water management and increase flood protection.

Hodzic, an Ulcinj-based environmentalist, says that both countries should strive to coordinate their efforts which are essential for ecosystem’s survival there.

“Spain has succeeded to reclaim its natural beaches in more than 400 locations. Hopefully Montenegro can do the same with the support of the EU.”

Dr Stephan Doempke, a German expert, proposed in 2008 to create a regional park of the River Bojana Delta, “a unique protected region with complex zoning and administration on the local level”. Describing the delta as the most important wetlands in the eastern Mediterranean, Doempke warned that, “if this area is not protected, it will seriously taint Montenegro’s reputation as a tourism-oriented country and ecological state.”

Albania fares no better

One third of Albania’s seacoast of 427 km is threatened by erosion, according to its Ministry of Tourism and Environmental Protection.

The country’s tourism minister Blendi Klosi said last November that the sea was swallowing an average 20 metres of beach every year. However, near the border with Montenegro the sea has washed off some 400 metres of shoreline over last 15 years.

“The sea is chipping off the shore,” Sherif Lushaj, an environmental expert at Tirana’s Polis University, told Albanian Top Channel TV. “This is nature taking revenge against human destruction of nature”.

Klosi said the European Commission, the EU’s executive arm, expected Albania, Montenegro and Croatia to come up with a joint project to protect the coastline.

Fears of flood every year

About 400,000 people live on both sides of the border. The fear of the Bojana spilling over is real. Sometimes the floods occur twice a year, inflicting huge damage to properties and farmlands south of Skadar in northern Albania, and a part of the municipality of Ulcinj in Montenegro.

“Apart from the problem of beach erosion, we saw the clogging of the estuary last year when the Bojana could not flow into the sea. Moreover the frequent floods in the area hint to inadequate response and efforts” said Marojevic. “It seems that the authorities rather focus on how to deal with the consequences then with the causes. Such reasoning and approach will cost us a lot at the end of the day”.

The 2020 Strategic Development Plan of the Ulcinj Municipality envisages regulation of the riverbed and construction of levees to protect from flooding.

Mustafa CANKA