“NOBODY’S LAND FOR NOBODY’S PEOPLE” - A Grey Story

Vedat, a Roma boy from Gjakova, Kosovo, was born in 1994 and was just five years old when the war erupted in his homeland. He was born with a severe infection in his leg, and due to the immense pain he was experiencing, his father, Fadil Behluli, decided to take him to the hospital one day. A few hours post-surgery, as he rested in his father’s lap, he witnessed three uniformed individuals dragging his dad away and shooting him in the hospital's backyard. He recalls the moment with great clarity even now. That was the final moment he shared with his father. Unbeknownst to Fadil, sending his son, who was suffering immensely, to the hospital would lead to a heartbreaking, tragic outcome—he would never return to his wife Hatem and their other children.

“The thing that I remember during the war in Kosovo is this: I was four and a half years old, five perhaps. It’s very vivid, I remember people being tense, and I know that I was sick because of my leg, I had it swollen or something like that, so my dad took me to the hospital, my mom wanted [to come] too, but my dad decided that she shouldn’t, so my dad took me to the hospital, and they fixed my leg. And after that, after the surgery was done and stuff, he put me to his lap. And he was trying to make me feel better even though I’m in pain. And there’s two or three guys walking down the hallway of the hospital with masks on. The views are vivid when I think about it sometimes, even when I see dreams everything is vivid. I can see a full picture, but when I talk about it it’s blurry. So, yeah, they walk into the hospital, they accidentally bump into my leg, I start crying, my dad tried to calm me down, but you know he got aggravated and he wants to be the hero, he gets up and says to them “hey watch where you’re going and bla bla bla”. So, they grab my dad, take us behind the hospital, and they shoot him. And are about to shoot me as well but one of the nurses comes into my rescue, she grabs me from them and the on this way she got a scratch on her arm, she puts me into her car and drives all the way to our house and takes me home and tells my mom what happened,” says Vedat who now is 30, for Center for Investigative Journalism in Crna Gora (CIN CG).

Shortly after, five years old Vedat and his mom Hatem who was five months pregnant with her fourth child at the time, left Kosovo to come to Montenegro and seek refugee and they haven’t gone back to live in Gjakova since. When asked how his life has been in Montenegro as a person with special needs he responded as follow:

“My life in Montenegro hasn’t been that great as a child because I got bullied, mistreated and all this stuff not only from friends and kids from school but…”, Vedat stops for a moment.

“Not so comfortable to say it but not only from friends or school [did I get bullied] but also from family side, trying to turn me down and make fun of me and whatnot”, told Vedat.

Beginning teenage years, Vedat got to go to the US through an international program that facilitated him by providing help with a very delicate process, which is getting a passport, in order for him to leave Montenegro and go to the United State for a few years.

“I didn’t live my teenage years here in Montenegro, I lived in the United States, so yeah. And the reason why I went to the United States is back in 2005 my aunt in United Kingdom she found some missionaries that work anywhere in United States and other countries. There’s this missionary, his name was Bob Hitchen, bless his soul he passed away a few months ago, I just found out. He came to my country, in Montenegro in 2005, they took pictures of me, they were asking questions, they were explaining to my mom and they stayed with me about a year to get the documents, because I had no documents. I didn’t have any Kosovo documents, I didn’t have any Montenegro documents, they did help me. And then in 2006 I got my Serbian passport and then I was able to go to the United States in March of 2006”, ended by saying Vedat.

Countless stories of horror, pain, and loss are behind thousands of Roma people who came to Montenegro from Kosovo’s war. What distinguishes the sufferings of this community from others? The emphasis they (did not) get. Indeed, every year and anniversary, along with numerous conferences and diplomatic visits overseas, we acknowledge and strive for justice for the Albanian civilians slain and massacred. However, this justice does not extend to the victims from minority communities, who, despite their existence, still bear the sorrow of their loss in their hearts. People rarely, if at all, remember them, nor do they construct stone memorials for them as there are for Albanian victims. In one instance, the Serb regime threw a grenade into Mitrovica's Green Market, killing civilians. That day, the grenade claimed the lives of seven people. The victims included six Albanians and a five-year-old Roma girl. The municipality raised a memorial in which they wrote the names of the victims after the war ended, but it only consisted of six names. Guess whose name was missing? Yes, that of the Roma child. Without this picture, which was taken on the exact day of the child's death, we wouldn't have found out of the child's existence in the first place.

People in Kosovo, especially the majority community there persecute and discriminate against this community, accusing some of them of siding with the occupier, specifically the Serbian forces, during the war. In Montenegro, the same community encounters various challenges, which we will explore further in this article.

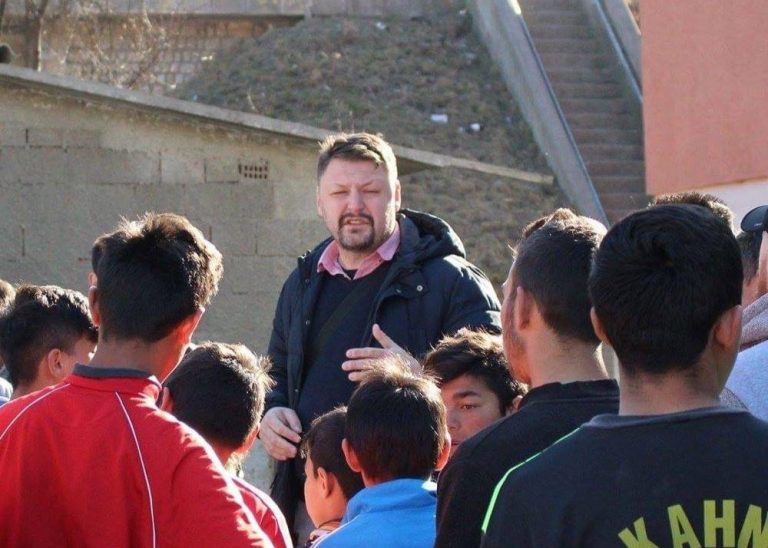

The CIN CG managed to contact Siniša Nadaždin (a picture of him on top of the article), a pastor at a local Protestant evangelical church who is one of the most renowned people who has worked, especially with the Roma community who have come to Montenegro after the war in Kosovo that took place in 1999. Nadaždin shared with us not only his experience in the past and how things progressed in the meanwhile but also how he regards the situation to be these days concerning this community in Montenegro.

“We need to talk about the way things were at the beginning, the way things were in the middle, and the way things are now. There was a process of 20 years. When they first arrived, they were definitely not welcomed. In the first couple of years, a lot of them migrated to Italy, going on these rafts. There was a catastrophe at some point. A lot of people died. I know people who personally went across the Adriatic that way. So, after a couple of years, thousand remained in Montenegro. I would say probably half of them, were here in Podgorica, in these two refugee camps, and around the refugee camps. How were they treated? They were treated awfully”.

Nadaždin claimed that once these refugees arrived on their new lands, no one wanted to assume responsibility for their well-being. He told us that everyone was more than happy to see them leave as soon as possible, which, to quite some degree, never happened.

“There were a lot of these legal loopholes. For example, the Camp Konik II that I mentioned, at some point ended up on no man's land. It didn't belong to UNHCR. The local government didn't want to accept it as their responsibility. So, there was some electricity over there, but then people started stealing electricity. So that whole place was out of any sort of norms, out of any sort of regulations. There was a community of 300 plus people where they were just left on their own. They had a landfill right across the wall. The Konik II camp was leaning against the wall of the landfill, so they were going to the landfill. The whole families dig overnight to get scrap metals. It is a very complicated story. But after it was obvious they were not welcomed, they were not embraced. And I want to say, probably nobody has ever said it out loud, but everybody was waiting for them just to go back home or move further, and they didn't. Several thousand stayed,” told Nadaždin for CIN CG.

Obtaining residency permits

Nadaždin told us about the help that the church staff gave to the Roma people who came from Kosovo while also mentioning how difficult the process of registering and applying for permanent or temporary residency permit was for them as well as how back then they tried to facilitate in this aspect too, other than in the “essential needs” such as food, clothing and medications. He told us that other than the process being too costly, too complicated and the procedures being too bureaucratic these people could apply for the residency only if they were in the refugee database, after bringing their Kosovar or Serbian documents, which they had to go and take in both respective countries.

This community lived in tents for almost a year

While looking towards their current situation and living conditions is important, it is as much important to remember that no other refugee from any country or any other ethnicity was put to live in the conditions that these Roma people were faced with upon arrival.

Nadaždin recalls his memories by noting “They lived in tents for almost a year. Nobody else. No other refugees were placed in, living conditions where they had no toilet facilities. They had to share all these toilets. They had to share water taps”.

He also remembers how for the conditions of the area in which they were put no one wanted to take responsibility, that at that point that land belonged to nobody, it was a nobody’s land. And Kosovo didn’t bother much and continues to be reluctant and avoidant about its once citizens, and the government of Montenegro including the local governance didn’t bother much, those Romani at that point were treated as nobody’s people.

The housing provided:

In 2019, two housing units were provided for the Roma and Egyptian population funded by the Regional Housing Program, but the apartment’s state seems not to be a success story. For this Nadaždin blames the lack of the law enforcement by institutional bodies of the state.

“But now, after obtaining their permanent residency, things have changed. Since 2015, 2016, 2017, they gave them these new apartments. There's almost like 250 apartments over there in that complex. I'm not sure how many people, at least 1,500 people live there. And they got these apartments cheap, almost for free. They were supposed to pay some tiny bit of rent, well, sort of a rent to the government, they don't do that. They don't pay a lot of other things, so the condition of these apartments is deteriorating”, described Nadaždin.

When asked what the government should do, the pastor said that there isn’t much affirmative action that the government can do. Instead, he said that the law enforcement can be an effective solution upon those who case the deteriorating state of these buildings and the damage of the lives of the other members of the community who are responsible citizens.

The inner dynamics

While commonly it is not stated, dynamics between the Roma community member who came from Kosovo during and after the war and those who were already here did arouse. Most of which, according to members of both parts, because that the latter felt that all the funds as well as the attention went to the first, making the domicile Roma citizens feel neglected and overshadowed.

The language barrier

When asked whether the situation is better with the Roma community in Kosovo or that in Montenegro, the pastor said that due to the language barrier being one of the factors, he sees the case of Kosovo as more promising compared to the situation or the Roma from Kosovo in Montenegro.

Here, there's always a language barrier. For some of them, Serbian is, like, their third language. For some of them, it's their second. So, some speak better, some speak worse. There's always going to be a wall between them and the rest of the population. So, because they came from where they came from, they also tend to self-isolate. When I think of Romani in Kosovo, there's probably less of that, that at some point, the chances for real integration are going to be greater. Here, it's going to be harder”, Siniša said while expressing his opinion.

People on these apartments not paying their fees

Vllaznim Batusha, an Egyptian who migrated from Kosovo after the war and currently resides in these apartments, expressed how challenging it is for these individuals to meet their financial obligations and support their families. He attributed this difficulty to the low employment rate, which results in a single member supporting a whole family, and the relatively low wages these individuals receive. However, he also asserts that maintaining one's space is a matter of personal responsibility. According to him, some families maintain their apartments in a responsible manner, while others cause significant harm to their neighbors by damaging mutual facilities.

CIN CG was there and witnessed very poor maintenance of these buildings.

Nadaždin describes the situation thoroughly while restating that law enforcement and order would’ve prevented this from being the case.

“You know, you see how people get wire from the wall, and then they plug in somehow to get their electricity. I mean, let's go down to the basement and see what happens there. There are frequent wildfires over there. So, when I say law enforcement, that's what I mean. There have to be some law and some order. Were they have to feel it. But now it's just survival. Now it's just getting electricity. To get electricity for their Internet. So, what I'm saying, people choose to pay for their Internet. They will not pay for their water”, said Siniša.

Although many things have progressed since the first days that the Roma community from Kosovo that came after the war was first placed in Montenegro cities, and their story, rather than a black-and-white one, is grey, by no means should it be seen as a success story. And the outside looks of their living areas now—once one digs deeper—are seemingly deceiving of what actually is the case. To this day, this part of the Roma community that lives in Podgorica, especially, is not integrated but rather lives in a ghetto, separated from the rest of the society. And when describing it as a ghetto, one could go further and put the adjective “modern” next to the noun. “Modern” because it looks nice from the outside, “modern” because it doesn’t look even close to the tents in which this community was first placed. And, yet, their living standards, on average, because even there one family differs from the other, are far from being compared to that of an average native Montenegrin family.

Why does this remain the case, and is the government supposed to do anything about it? According to Siniša, it is part of human’s nature to try and find the easiest, cheapest way out; however, it is the government that should not allow people to continue to live in these conditions.

“So, there are these situations where there's also poor management, poor culture of using things. You can't improvise forever. It works for a period of time, but then, people try to hook up this wire with this wire and that wire with that other wire. I've seen some houses over there where they try to save money on everything. So, they get windows from the garbage or they find pieces of wire that they connect together, and those pieces of wire that are poorly connected there, they're inside of the walls. First of all, people shouldn't be allowed to live like that. There has to be government incentive, but also there has to be government regulation. You can't just let people do whatever they want. And people will always try to find easy way out. In this case, cheaper way out”.

The political representation

Shortly put: there isn’t one. The Roma community does not currently hold seats in the Montenegrin parliament. For years now, a quota has guaranteed political representation for most other non-majority communities but not to the Roma and Egyptian communities.

Writes: Hanmie Lohaj

"This article has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of CIN CG and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union."

This story is a poignant reminder of the resilience of marginalized communities like the Roma refugees. Vedat’s journey highlights not only the personal struggles of war and displacement but also the broader systemic issues that still need attention. It’s crucial that stories like these are told to inspire empathy and action.

Very touching & insightfully written.

Hoping people will be able to empathize and highlight those stories more and more until a proper solution comes.

Kudos to the writer. Great job!